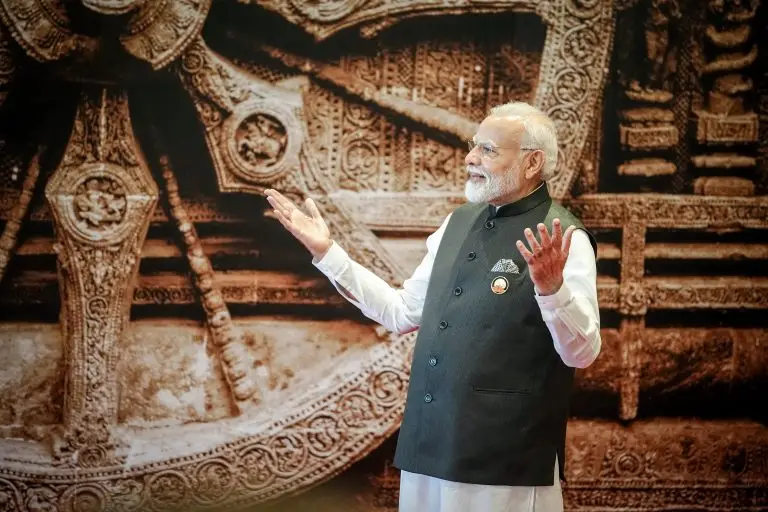

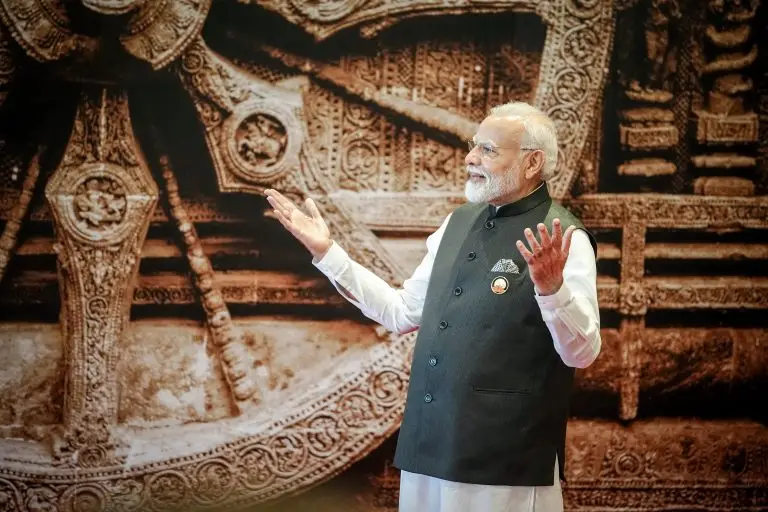

[동아시아포럼] 인도 ‘수입 대체 산업화’ 정책에 대한 오해와 전망

기존 산업정책, 비효율적 산업구조의 한계로 실패 2014년 '메이크 인 인디아' 이후, 개방·협력 강조 규제 완화, 유연한 노동·자본시장 조성 등에 중점

[동아시아포럼]은 EAST ASIA FORUM에서 전하는 동아시아 정책 동향을 담았습니다. EAST ASIA FORUM은 오스트레일리아 국립대학교(Australia National University) 크로퍼드 공공정책대학(Crawford School of Public Policy) 산하의 공공정책과 관련된 정치, 경제, 비즈니스, 법률, 안보, 국제관계에 대한 연구·분석 플랫폼입니다. 저희 폴리시코리아(The Policy Korea)와 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

1950년대부터 인도는 자급력 확보를 위해 수입 대체 산업화(import substitution industrialisation, ISI) 정책을 추진해 왔다. 하지만 ISI 정책은 단기적으로는 일정한 성과를 거뒀지만 장기적으로는 공기업과 소기업에 유보된 산업 활동, 낮은 투자 효율성과 만성적인 GDP(국내총생산) 저성장 등으로 인해 대부분 실패로 돌아갔다. 이후에도 자국 시장에 대한 보호정책으로 산업 경쟁력이 약화되고 비효율적인 산업구조의 부작용이 드러나자, 1980년대부터는 점차 경제 개방과 자유화를 토대로 한 정책으로 전환한 바 있다.

1950년대 이후 ‘수입 대체 산업화’ 통해 산업 육성

2014년 시작된 ‘메이크 인 인디아(Make in India)’ 기조를 기점으로 인도의 산업정책은 자국의 산업을 보호하고 촉진하는 데만 한정하지 않고 외국 기업을 유치해 인도의 제조업을 세계적으로 경쟁력 있는 산업으로 만드는 것을 목표로 하고 있다. 현재 인도 정부가 추진하는 산업정책은 앞서 실패한 ISI 전략과 달리 협력국과의 경제 통합과 개방을 추구하는 동시에 국내 산업의 성장과 일자리 창출을 도모한다는 점에서 성공 가능성에 대한 기대감이 높아지고 있다.

하지만 ISI 옹호론자들은 현재 인도 산업정책의 목표를 단순히 국내산업을 육성·유지하는 데만 초점을 두고 낙관적인 전망을 내놓고 있다. 인도의 수입은 1970년 GDP의 5%를 넘지 못했지만 30여 년이 지난 2022년에는 21%의 비중을 차지했다. 그동안 국내 수요가 많은 다양한 품목에서 대량 수입이 이뤄지면서 수입이 늘어난 것이다. 이에 대응해 인도 정부는 대량 수입으로 수요를 충당하는 산업에서 재화의 수입을 제한함으로써 국내 기업이 해당 제품이나 유사한 대체품을 생산하도록 유도해 왔다. 이 기간 인도는 국내 수요가 많은 핵심산업을 보호·육성하기 위해 무역장벽을 강화했고 철강, 알루미늄, 비료, 화학물질, 자동차 등의 산업을 성공적으로 육성할 수 있었다.

단기간에 국내 산업을 육성한다는 점만 본다면 현재 추진하는 ISI 전략의 성과도 앞선 정책들과 다르지 않다. 하지만 산업정책의 성공을 논하기 위해서는 정책기조와 수단의 차이에 대해 살펴볼 필요가 있다. 현재의 ISI 정책은 투자 라이선스, 대량 생산, 외국자본 진입, 기술 수입 등 노동·자본시장의 규제를 완화한 새로운 경영 환경을 조성하는 데 초점을 두고 있으며 이는 산업정책의 장기적인 성공에 결정적인 역할을 할 것으로 보인다. 기업의 입장에서는 규제 완화와 유연한 경영 환경을 기반으로 보다 빠르게 변화에 대응할 수 있으며 소비자 입장에서는 수입품 가격과 국내 생산비용 간의 격차를 줄여 수입관세로 인한 시장의 왜곡과 사회적 후생손실(welfare loss)을 줄일 수 있기 때문이다.

특정 산업에 대한 지원은 다른 산업의 발전 억제해

산업정책의 진정한 성공은 보호무역을 통해 자국의 산업을 육성하고 유지하는 것이 아니라 국가 전체의 경제 성장을 가속화할 수 있는 역량 강화와 체질 개선으로 평가받아야 한다. 이러한 측면에서 ISI 정책은 논란의 여지가 있다. 국가가 보호·육성하는 산업의 경우 국내 생산이 해외 생산이나 수입보다 더 많은 비용이 투입되는 반면, 국가가 보호하지 않는 산업은 국내 생산 비용이 수입보다 저렴한 경우가 많다. 이러한 상황에서 인위적으로 자국의 산업을 보호하는 조치들은 고비용 산업을 지원함으로써 결국 저비용 재화의 생산에 투입해야 할 자원을 이동하게 만들어 산업 전반의 효율성을 저하시킬 가능성이 있다.

흔히들 정책 결정자들은 수입 대체 산업화를 성공적으로 추진하는 동시에 수출 활성화를 통해 GDP를 증대시킬 수 있다고 믿지만, 이는 자원이 한정돼 있는 데다 특정 시점에는 그 자원이 고갈된다는 점을 고려하지 못한 결정이다. 즉 국가가 보유한 생산요소와 자원의 한계로 인해 특정 산업을 지원하는 정책은 곧 다른 산업을 억제하는 정책이 될 수밖에 없다. 실제로 ISI 정책을 추진한 국가의 총수입·수출 데이터를 10년 이상의 기간 동안 추적해 보면 총수입이 감소하는 것처럼 보인다. 그러나 총수출도 함께 감소하는 것을 확인할 수 있다. 보호무역을 위한 수입세가 수출 재화를 비롯해 수입 대체품의 수익을 약화시킨 것이다. 특히 환율이 강세일 때는 수출 기업의 이윤이 더욱 크게 감소해 산업 전반을 위축시킨다.

최근에는 새로운 기술의 적용으로 산업환경이 크게 변화하면서 ISI 정책에 부정적인 영향을 미치고 있다. 이 중 첫 번째는 운송·통신기술의 발전으로, 먼 거리로 재화와 정보를 전달하는 비용이 크게 감소한 것이다. 두 번째는 스마트폰·태블릿 등 대량 소비를 위해 만들어진 복합제품들의 경우 생산과정이 세분화·전문화되면서 특정 부품이나 공정을 수행하는 전문기업들이 밸류체인을 구축해 생산 효율성을 제고하고 있다는 점이다. 이러한 변화를 통해 혁신 기술의 도입, 제품 디자인과 설계, 부품 제조와 조립 등 각 생산 공정을 비용의 이점이 있는 여러 나라로 분산시켜 효율성을 제고한다. 일례로 아이폰은 R&D(연구개발) 등 기술 혁신, 디자인, 부품의 제조와 조립 등이 20여 개국에 걸쳐 이뤄졌다. 이러한 국가별 특화 전략에 있어 전통적인 ISI 정책은 장애가 될 가능성이 높다.

보호무역 벗어나 파트너십 강화 등 체질 개선 노력

다만 ISI 전략에 대한 회의론을 인도 경제 전망에 대한 비관주의로 오해해서는 안 된다. 비록 ISI 정책으로 회귀하는 과정에서도 인도 정부는 거의 모든 측면에서 적절한 조치를 취해왔다. 경제개혁을 통해 경직된 재화·생산요소 시장을 개선했을 뿐만 아니라 도로, 철도, 수로, 교각, 공항, 항구 등 국가기반시설은 물론 디지털 플랫폼 등 기술 산업을 위한 인프라도 중점적으로 구축해 왔다. 인도의 중앙 정부와 주정부도 다국적 기업을 유치함으로써 ‘차이나 플러스 원(China Plus One)’ 전략에서 중국의 대안이 되기 위해 노력해 왔다. 인도 정부는 글로벌 시장에서의 네트워크 중요성을 잘 알고 있다. 이를 위해 경제적 특성이 유사하거나 이해관계를 같이 하는 국가들과의 자유무역협정(FTA)을 확대함으로써 다국적 기업들에게 매력적인 생산기지로 거듭나기 위해 노력하고 있다.

이러한 맥락에서 인도 서쪽으로 인도-중동-유럽 경제회랑(IMEC)이 출범했다. 인도는 이를 통해 EU·영국과의 FTA를 성공적으로 마무리할 수 있을 것으로 기대하고 있다. 인도 동쪽에 위치한 협력국과의 파트너십은 더욱 중요하다. 전문가들은 중국 주도의 거대 다자 자유무역협정(FTA)인 ‘역내 포괄적 경제동반자협정(RCEP)’에 가입하는 것이 가장 이상적이라고 평가했지만 중국과의 정치적 이슈로 인해 이러한 논의는 더 이상 무의미해졌다. 지난해 중국 티베트 남부와 인도 동부 국경 분쟁 지역에서 2년 만에 무력 충돌이 발생한 데 이어 최근 중국 정부가 분쟁 지역을 자국 영토로 기재한 지도를 발간하면서 양국 관계가 더욱 악화됐기 때문이다. 이런 상황에서 인도는 주변국과의 파트너십을 강화해 중국을 견제하는 방안을 모색하고 있다. 현재로서 가장 좋은 옵션은 동남아시아국가연합(ASEAN)과의 FTA를 확대하고 포괄적·점진적 환태평양경제동반자협정(CPTPP)에 가입하는 방안이다.

앞서 언급했듯 ISI 전략에 초점을 둔 그간의 산업정책은 분명 특정 제품의 수입을 감소시켰다. 하지만 수입과 수출을 한꺼번에 보면 전혀 그렇지 않다. 인도의 상품 수입은 코로나19 이전인 2018년 5,180억 달러(약 673조4,000억원)에서 2022년에는 7,210억 달러(약 973조3,000억원)로 계속 증가했다. 같은 기간 상품 수출은 3,370억 달러(약 438조1,000억원)에서 4,560억 달러(약 592조8,000억원)로 상승했다. 서비스 수출은 더욱 좋은 성과를 냈다.

10년 후 산업정책의 성과를 평가할 때 ISI 정책의 추종자들은 자유무역주의자들의 반대에도 불구하고 수입 대체 산업화를 통해 인도 경제가 발전할 수 있었다고 주장할 것이다. 아시아에서는 여전히 한국, 대만, 중국, 싱가포르 등 성공한 산업국가들의 성장에 ISI 정책이 기여했다는 신화가 존재하기 때문이다. 하지만 ISI 전략에 대한 이들의 맹목적인 믿음은 사실상 근거가 없다. 오히려 보호무역 중심의 ISI 정책을 포기하고 개방과 협력 중심의 수출 지향 산업화 전략을 채택하는 것이 성공을 위한 열쇠가 될 수 있다.

원문의 저자는 컬럼비아대학(Columbia University) 경제학과의 아르빈드 파나가리야(Arvind Panagariya) 교수와 재그디시 바그와티(Jagdish Bhagwati) 교수입니다.

The false promise of import substitution industrialisation in India

Expectations that import substitution in India might succeed this time around are premised on the twin assumptions that the policy is being implemented in a very different environment from the past and that the instruments being deployed are also different. But the country’s previous import substitution episodes also differed from one another along these dimensions and every one of them failed.

If proponents for import substitution industrialisation judge its success purely on its ability to establish and sustain the targeted industry, one could concede to their argument. With merchandise imports at 21 percent of GDP in 2022 as opposed to less than 5 percent in 1970, the economy offers considerable scope for import substitution. The large volumes of imports of many products testify to the existence of a domestic demand for them. Denying entry to their imports will create space for the emergence of domestic suppliers of those same products or close substitutes.

But such success would be no different from the previous rounds of import substitution, which India pursued for several decades after independence. During that era, India successfully established numerous industries — including steel, aluminium, fertiliser, chemicals and automobiles — behind a protective wall.

This time — with no investment licensing, less rigid labour and capital markets, no restrictions placed on large-scale production, freer entry of foreign investors and the absence of restrictions on technology imports — the domestic supply response is likely to be quicker. The difference between import prices and domestic production costs is also smaller, limiting the welfare loss due to distortion caused by the import tariffs.

The true success of import substitution must be judged not by its ability to create and sustain protected industries, but by its capacity to accelerate the entire economy’s growth, however. The case for import substitution crumbles along this metric. Products that receive protection often cost more to produce at home than abroad, while the opposite is true of unprotected products. Protection supports the higher-cost products by incentivising resources to move into them and out of the lower-cost products.

A common fallacy among policymakers is that import substitution can be pursued successfully alongside export promotion to boost GDP. That fails to appreciate that with a fixed volume of resources available at a point in time, supporting a subset of industries means discouraging others.

An examination of the total import and export series for any country over a 10-year period or longer demonstrates that when import substitution successfully cuts the total imports, it also cuts total exports.

Import duties on inputs are one channel through which import duties undermine exports and the final import substitute products. Such duties reduce the profitability of final goods using the inputs, whether they are exported or sold domestically. A more general channel through which tariffs undermine exports is real exchange rate appreciation. Currency appreciation results in the exporter earning fewer Indian rupees for every US dollar’s worth of exports.

Two mutually reinforcing recent developments have further undermined the success of an activist import substitution industrialisation policy. First, as a result of advances in transportation and communication technologies, the cost of moving goods and information over long distances has decreased significantly. Second, modern technology has given rise to complex products of mass consumption, such as smartphones and tablets, with substantial design and information-related content. It has also made it possible to break up the production processes of old and new products more efficiently.

These developments have meant that efficiency is achieved by locating product innovation, product design, production of components and assembly across many nations, depending on their cost advantages. The iPhone is a good example — its innovation, design, manufacture of numerous components and assembly are spread over two dozen countries. Import substitution industrialisation discourages industrialisation by placing obstacles in the way of this international specialisation.

Scepticism towards import substitution industrialisation should not be mistaken for pessimism about India’s economic prospects. Despite returning to a mild form of ISI, India has been taking the right steps in nearly all other dimensions. In addition to removing rigidities in the product and factor markets through liberalising economic reforms, it has been building its infrastructure at breakneck speed, focusing on roads, railways, waterways, bridges, airports, ports and digital platforms.

The central government and some state governments have also been courting multinational corporations to become the ‘Plus One’ in their ‘China Plus One’ strategy. Pursuit of import substitution industrialisation notwithstanding, these administrations are cognisant of the importance of engaging with world markets. In this context, India can enhance its appeal to multinational corporations as the ‘Plus One’ destination by engaging like-minded countries in free trade agreements (FTAs).

To its west, India has launched the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor. Its impact can be greatly amplified by the conclusion of FTAs with the EU and the United Kingdom. India’s engagement with its partners to the east is even more important. Ideally, this would have been best accomplished by joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). But this has lost political salience in the wake of the recent eruption of the border dispute with China. The next best option is to strengthen the FTA with ASEAN and seek entry into the other large FTA of the region, The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. Without these moves, India risks giving China a free hand in the region.

The effect of the Indian policy regime, which includes import substitution, has been to cut the imports of certain products, but not imports and exports taken as a whole. Total merchandise imports have continued to flourish, rising from a pre-COVID-19 peak of US$518 billion in 2018 to US$721 billion in 2022. Merchandise exports have risen from US$337 billion in 2018 to US$456 billion in 2022. Services exports have performed even better.

If history is any guide, ten years from now import substitution devotees will claim that India’s success was due to its pursuit of import substitution, despite contrary advice from free trade ideologues. After all, the myth of industrial policy’s contribution to the success of South Korea, Taiwan, China and Singapore continues to endure. But this claim is incorrect. India will succeed not because of import substitution, but in spite of it.

![[동아시아포럼] 백두산 과학외교, 대북 협력 가능성과 전망](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/11/기사-7.webp)

![[동아시아포럼] 대학 랭킹을 이용한 호주 대학의 ‘유학생 유치 전략’](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/12/기사.webp)

![[동아시아포럼] EU의 지속가능한 순환섬유 전략과 동아시아의 도전](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/11/기사-11.webp)

![[동아시아포럼] 아시아의 인구 감소 해결책, 늦진 않았지만 낭비할 시간도 없다](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/06/베이징_동아포_20230627.jpg)

![[동아시아포럼] 한국 대학의 세계화 전략과 인도 시장 진출](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/02/india_EAF_20240229-768x512.jpg)

![[동아시아포럼] 새로운 대전략을 찾는 일본](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/11/2022-11-06T092657Z_51102667_RC29GX9YB2TC_RTRMADP_3_JAPAN-DEFENCE-768x563-1.jpg)