[동아시아포럼] 中 공산당의 발전모델, 인도·태평양 지역 국가에 적용 가능한가?

덩샤오핑 이후 30년간 中의 고속성장, 국제사회에 기여 최근 자유주의와 개인의 희생 강요한 전체주의로 전환 사회주의 성공 강조하는 中 정치적 내러티브는 경계해야

[동아시아포럼]은 EAST ASIA FORUM에서 전하는 동아시아 정책 동향을 담았습니다. EAST ASIA FORUM은 오스트레일리아 국립대학교(Australia National University) 크로퍼드 공공정책대학(Crawford School of Public Policy) 산하의 공공정책과 관련된 정치, 경제, 비즈니스, 법률, 안보, 국제관계에 대한 연구·분석 플랫폼입니다. 저희 폴리시코리아(The Policy Korea)와 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

전 세계 국가들이 대립과 협력, 경쟁과 공조의 균형을 강조하고 있는 가운데, 주요국들은 경제, 기술, 군사 등 다양한 분야에서 치열하게 경쟁하는 동시에 글로벌 현안 대응과 공동 성장을 위해 협력하고 있다. 이러한 상황에서 지난 30년간 중국의 경제 성장을 이끌어온 공산당의 발전 모델이 세계의 주목을 받고 있다.

1978년 덩샤오핑, 자본주의 접목한 개혁·개방 노선 채택

중국 공산당의 발전 모델은 급속한 경제 성장을 이뤄내는 등 가시적인 성과가 있었지만 구체적으로 살펴보면 공산당 지도자들의 정치적 목표를 달성하는 데 초점을 두고 있다. 최근 일각에서 제기된 “과연 공산당의 전략을 인도·태평양 지역 국가에도 적용할 수 있을까?”라는 질문에 대한 답은 중국 공산당이 추진한 ‘실행가능한 발전(viable development) 전략’에서 찾을 수 있다. 실행가능한 발전이란 국가의 특성과 상황을 글로벌 스탠다드와 조화시킴으로써 자국민의 삶의 질을 제고할 수 있는 기능적인 정치·경제 시스템을 구축하는 전략을 말한다.

중국의 발전 모델 탄생은 1970년대로 거슬러 올라간다. 1970년대 후반부터 1990년대 후반까지 이어져 온 덩샤오핑의 개혁·개방 정책은 사회주의 국가에 자본주의 시장경제를 접목한 발전 모델을 만들어 냈다. 이 시기 중국은 사회주의 체제임에도 자유주의·중상주의(liberal and mercantilist) 정책을 수용하고 외국의 자본·기술·시장에 접근할 수 있는 경제특구를 지정·운영함으로써 경이로운 경제 발전을 이뤘다. 이러한 공산당의 발전 모델은 ‘세계의 공장’으로 불리는 제조강국을 탄생시키면서 중국을 넘어 국제사회에 기여했다. 세계은행(WB)도 “중국 공산당이 1978년 개혁·개방 노선을 채택한 이래 중국의 연 평균 경제성장률이 9%를 넘어섰으며 8억 명 이상의 국민들이 빈곤에서 벗어났다”며 그 성과를 인정한 바 있다.

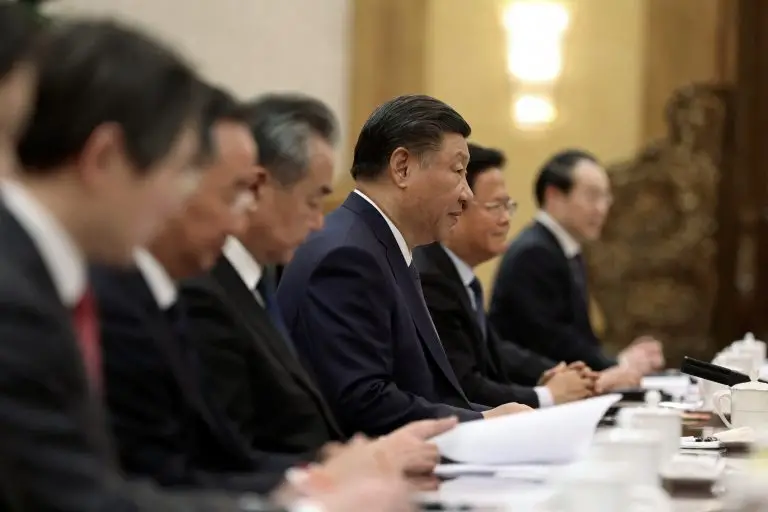

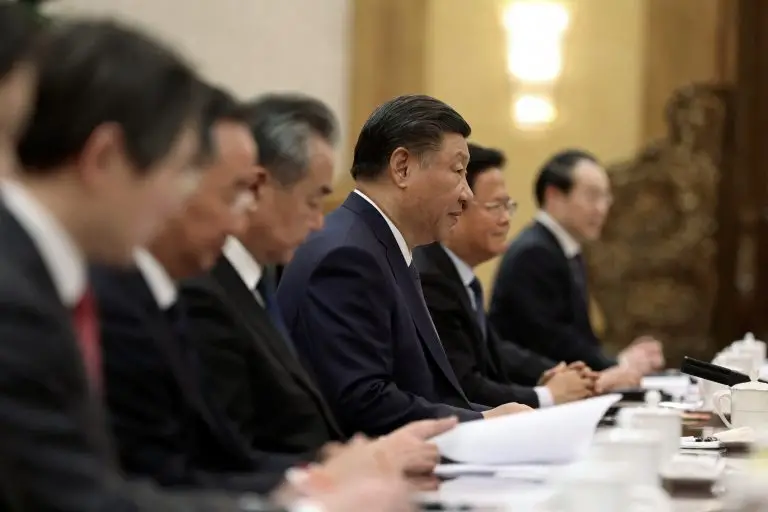

시진핑 주석이 정권을 잡은 이후 중국은 ‘중화민족의 위대한 부흥(great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation)’을 비전으로 제시하고 ‘일대일로 이니셔티브(Belt and Road Initiative, BRI)’와 같이 여러 국가와의 연결과 협력을 강화하는 전략을 추진했다. BRI는 동남아시아·중앙아시아·서아시아·아프리카·유럽 잇는 인프라·무역·금융·문화 교류의 경제벨트로 추진 기간만 150년에 달하는 중국의 장기 프로젝트다.

하지만 현재 중국의 발전 전략은 ‘실행가능한 발전’이란 슬로건이 무색하게 중국의 특수성과 세계 질서를 조화시키지 못하고 있다. 오히려 중국 공산당은 미국와 중국의 2강 구도에서 세계 질서를 자국에 맞게 수정하는 전략을 시도하고 있다.

시진핑 집권 이후 공산당, 당의 이익과 권력 유지 우선

시진핑 집권 이후 중국 공산당은 개헌을 통해 주석·부주석을 2연임까지만 가능하도록 제한한 조항을 폐기하는 등 중앙집권적 권력을 강화하고 있다. 올해 3월 역사적인 3선 집권에 성공한 시진핑 주석은 정치적 라이벌을 숙청하고 공산당 간부들을 무더기 징계하는 등 인권 침해마저 서슴치 않고 있다. 정부의 규제를 비판했던 알리바바의 창업자 마윈에 대한 탄압 등에서 볼 수 있듯이 공산당은 권위주의에서 전체주의로 전환하고 자본주의와 시장경제가 아닌 당의 이익과 권력 유지를 우선시하는 모양새다.

이제까지 보여준 중국의 성장과 변화가 시진핑 주석의 주장처럼 진정한 사회주의의 승리인지, 아니면 덩샤오핑의 개혁·개방이 외국 자본·기술의 수용과 세계화, 자유주의 원칙에 기반한 시장경제의 성과인지에 대해서는 의견이 분분하다. 중국의 발전이 자유주의와 시장경제를 수용한 성장인지, 아니면 사회주의 유토피아를 위한 희생이 기반이 된 것인지 아직 명확하지 않기 때문이다. 그도 그럴 것이 사회주의 정부가 주도하는 자본주의는 수백만 명을 빈곤에서 벗어나게 했지만 한편으론 당의 통제라는 정치적 딜레마에 빠지게 했다.

중앙집권적인 사회주의에 기반하면서도 자본주의와 시장경제를 수용한 중국의 발전 모델이 세계적으로 적용 가능한지 진단하기 위해서는 공산당의 권한, 고립주의(isolationism)와 정치적 통제, 경제적 자유주의, 글로벌 시장과 자원에 대한 접근성 등을 종합적으로 살펴볼 필요가 있다. 하지만 중국의 모델은 민주주의와 인권에 대한 위협, 부채의 함정, 친환경 기조와 지속가능성 등 인도·태평양 지역 국가들이 직면한 현안을 해결하기엔 한계가 있다.

인도·태평양 지역, 공조·협력 기반의 독자 모델 모색해야

최근 중국은 공산당의 권한과 정치적 통제력을 유지하기 위해 자국의 발전과 관련한 내러티브를 사회주의의 성공으로 돌리는 한편, 자유주의·자본주의·민주주의와 인권을 위협하는 등 세계 질서에 도전하고 있다. 고성장의 비결로 사회주의의 승리를 강조하는 중국의 정치적 서사는 일당제 집권여당인 공산당의 장기 집권과 생존을 위한 전략일 가능성이 높다. 이뿐 아니라 오히려 공산당이 자신들의 정치적 헤게모니를 공고히 할수록 자유주의 시장경제를 훼손하고 개인에 대한 탄압과 희생을 요구하는 사례가 많아지고 있다.

중국의 접근방식은 패권주의적이며 나아가 전 세계의 안정을 위협한다. 이에 자유주의 국가들은 중국 공산당의 위협으로부터 자국을 보호하고 방어하기 위한 조치를 취하고 있으며, 일각에선 갈등이 심화될 경우 신냉전의 시대가 도래할 것이란 우려도 나온다. 인구와 국토의 규모가 큰 중국의 특성상 공산당의 발전 모델이 얼마나 효과를 유지할 수 있을지는 알 수 없다. 하지만 중국보다 규모가 작은 국가들은 공산당처럼 중앙집권적 권력을 유지할 능력이 없는 만큼 자유주의 원칙에 기반한 글로벌 무역시장이 필요하다.

중국 공산당의 발전 모델은 알려진 것보다 훨씬 복잡하다. 이렇다 보니 중국은 과거 사회주의 시대에서 현재까지 여러 변화와 개혁을 통해 발전했음에도 때때로 경제성장의 신화나 폐쇄적인 전체주의의 일면만으로 오해를 받기도 한다. 최근 들어 강대국 간 경쟁이 치열해지는 상황에서 중국의 발전 전략은 인도·태평양 지역 국가들에 중요한 시사점을 남긴다. 다만 이들의 전략을 다른 국가에 적용할 수 있는지에 대한 논의에는 미묘하면서도 역동적인 국제 정세에 대한 세심한 이해와 전략적 판단이 필요하다. 먼저 인도·태평양 지역 국가들은 자국의 민주주의와 안보를 위해 국제사회를 위협하는 패권주의와 지역의 통합을 저해하는 개입에 대항해야 한다. 나아가 나라의 고유한 발전 모델을 추구하는 동시에 각국의 목표와 세계 질서에 부합하는 외부 지원을 모색함으로써 국가 간 공조를 강화할 필요가 있다. 이 과정에서 인도·태평양 지역 국가들은 주변국들과 미·중 2강 체제 속 갈등과 경쟁에 대한 이해를 같이함으로써 지역의 독자적인 정책을 추구할 수 있을 것으로 전망된다.

원문의 저자는 본드 대학교(Bond University) 사회·디자인 학부의 조나단 핑(Jonathan Ping) 교수입니다.

Is the CCP’s development model viable in the Indo-Pacific?

In a world marked by great power competition but striving for global development, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) development model has garnered significant attention. But can the development model that has served Chinese leaders’ policy and political goals so well be generally applied across the Indo-Pacific to similar ends?

The answer to this question lies in various aspects of the model of ‘viable development’ that the CCP has embraced.

Viable development is a concept that refers to the construction of a functioning political economy that aligns domestic characteristics with the globalising world order to advance the well-being of those living within the affected state. Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the late 1970s created a socialist state-directed market capitalist development model in China.

This model has benefitted China and the global community as acknowledged by the World Bank, with statements such as: ‘Since China began to open up and reform its economy in 1978, GDP growth has averaged over 9 percent a year, and more than 800 million people have lifted themselves out of poverty’. From socialist economics to embracing liberal and mercantilist policies and establishing special economic zones to gain access to foreign capital, technology and markets, China’s development is remarkable.

Xi’s dream for China revolves around the ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’. Under his leadership, China has launched development projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to enhance connectivity and cooperation across multiple states. While the initiative is promising, it does not align domestic considerations with the globalising world order. Instead, it attempts to revise the global order to fit its domestic attributes.

Under Xi’s leadership, the CCP has eliminated the two-term limit, centralised power, purged political rivals, disciplined elites and continued to commit human rights violations. This shift from authoritarianism to totalitarianism has imposed party interests over the market and capitalism, as exemplified by the treatment of business leaders like Alibaba’s Jack Ma.

This raises questions about whether China’s transformation is truly a triumph of socialism as Xi insists, or the result of access to foreign capital and technology as well as trade via the globalising liberal rules-based market brought about by Deng. While socialist state-directed market capitalism has lifted millions from poverty, it also poses a dilemma for the Chinese population. They are caught in a political conundrum between poverty and party control — whether they have developed through less intervention by the state and greater freedom within a global market capitalist economy or through sacrifice for the socialist utopia.

When evaluating whether the CCP’s socialist state-directed market capitalism is viable as a global development model, it is important to highlight that CCP development in China hinges on party authority, political control through isolationism, economic liberalism and the continued access to global resources and markets. The model presents challenges in the Indo-Pacific region, with political issues like threats to democracy and human rights as well as economic concerns such as debt traps and environmental sustainability.

The CCP’s ‘how-to-develop narrative’, which attributed success to socialism challenges the global order — posing threats to liberalism, capitalism, human rights and democracy, since it requires political control and party authority. This also raises questions about a potential new Cold War, as states dependent on the stability of the present globalising liberal rules-based market system attempt to protect it.

The CCP’s present narrative, which attributes its development to the socialist model, threatens its own development and that of other states. This politicised approach to development primarily serves its own survival as an elite vanguard political party. Yet, to succeed, it compromises economic development and requires individual sacrifices, making it less viable.

Beijing’s approach is hegemonic and threatens global stability. While the CCP may be able to sustain China’s domestic development due to China’s size, smaller states don’t have this same capacity and require the rules-based liberal global market which underpins global development. Countering hegemonies and ensuring the security of democratic Indo-Pacific states may require the formation of mercantilist blocs.

States in the Indo-Pacific region must pursue unique development models, seek external support that aligns with their goals and the globalising world order and resist interventions that undermine their unity. Creating a common understanding of the China–US rivalry and passing region-wide policies can enable collaborative interaction for the benefit of viable development.

The CCP’s development model is complex and often misunderstood. In an era of great power competition, the CCP’s approach to development has far-reaching implications for China and the Indo-Pacific. This discussion underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of the dynamic landscape and the importance of formulating strategic responses to these challenges.

![[동아시아포럼] 내년 2월로 예정된 ‘제13차 WTO 각료회의’에 주목하는 이유](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/11/2022-06-12T100448Z_2137354140_RC2AQU9M46GL_RTRMADP_3_TRADE-WTO-PRESSER-500x342-1.jpg)

![[동아시아포럼] 인도의 노동개혁, 수입대체 전략의 한계 넘어설 수 있나?](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/01/India_EAF_20240118.webp)

![[동아시아포럼] 호주-인도네시아 자원 동맹, 구축과 성공의 과제는](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/11/East-Asia-Forum.jpg)

![[동아시아포럼] 윤석열 정부의 정치기반 확보를 위한 사투](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/11/0711-EAF.jpg)

![[동아시아포럼] 中 부동산 위기, 고도 성장 신화의 끝일까?](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/12/end-of-China-miracle_동아시아포럼_20231227.webp)

![[동아시아포럼] 자민당 비자금 스캔들 속 기시다 총리의 생존 투쟁](https://pabii.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/12/기사-6.webp)